When 'Ford freed Poland': Debate lessons from 1976 for Trump, Clinton

A presidential debate feels less like Debate Night than Fight Night, one legacy of a showdown that occurred when most of this year’s audience was too young to vote.

As Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton prepare for their opening debate on Sept. 26 in Hempstead, N.Y., another contest 40 years ago offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong.

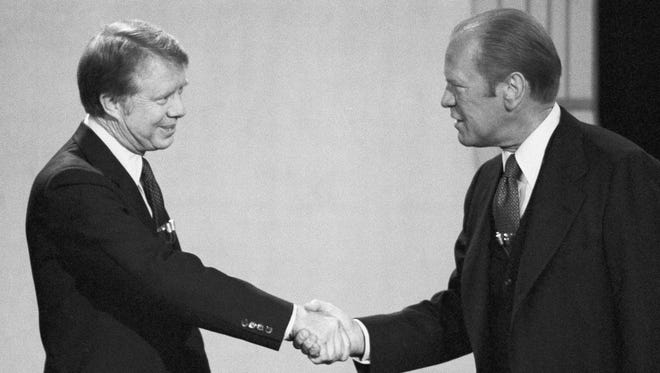

In 1976, President Gerald Ford, who’d challenged Democratic nominee Jimmy Carter to a televised debate, was figuratively knocked out — by his own punch.

Inexplicably, the president said Eastern Europe was not dominated by the Soviet Union, which in fact had three Army divisions in Poland alone. In November he lost by a hair. “We won the election that night,’’ says Carter’s communications director, Gerald Rafshoon.

Ever since, many Americans have watched these general election debates with dry mouths and moist palms, as if ringside at a heavyweight bout. And they’ve waited (largely in vain) for something like 1976, when, Carter running mate Walter Mondale still jokes, “Ford freed Poland.’’

Now, says Alan Schroeder, author of a study of presidential debates subtitled 50 Years of High-Risk TV, “Everybody wants their guy to land a knockout blow’’ — a faux pas or zinger that will decide not only the debate, but the election.

Election flashback quizzes: 10 ways to distract yourself from the 2016 race

2016 general election debate schedule

New tradition born

Although the 1976 debates are known for Ford’s gaffe, they also established an extra-constitutional political tradition: Every four autumns, the major presidential nominees stand on an auditorium stage for 90 minutes before a live audience answering questions.

Many people think that tradition started in 1960, with John Kennedy and Richard Nixon. But those debates were the last for 16 years. And Kennedy and Nixon debated in a TV studio with no audience; sat down when not speaking; and only went for 60 minutes.

Neither of the 1960 debaters was the incumbent. It still wasn’t clear whether the commander in chief had to debate, or should. In 1964, ’68 and ’72, Presidents Johnson and Nixon, who didn’t want to debate for political reasons, avoided doing so at no political cost.

That’s one reason 1976 was so ironic: Ford didn’t have to debate. Also, he stumbled on foreign policy, which both campaigns considered his forte, and despite having practiced far more rigorously than Carter.

All of which might give pause to the Clinton and Trump campaigns, determined to prepare for every contingency and control every detail.

“We always learn something big about candidates that we didn’t expect to learn,’’ says Mondale, who participated in the presidential debates of 1984 and the inaugural vice presidential debate in 1976. “There’s no formula to guarantee you won’t flub it. So beware!’’’

'No red flag' after gaffe

In the summer of 1976, Ford was in political trouble. He was president only because Richard Nixon resigned during the Watergate scandal; he alienated many voters by pardoning Nixon; and he barely survived a primary challenge by Ronald Reagan. After the Democratic convention, he trailed Carter in polls by more than 30 points.

So Ford decided he needed to debate Carter, who’d hoped to debate all along, and inserted a challenge into the prepared text of his convention speech.

After weeks of the sort of haggling over the details that would itself become a tradition, the fall debates (under the auspices of the League of Women Voters) were set for Philadelphia, San Francisco and Williamsburg, Va., at the College of William & Mary.

Ford, considered the less telegenic candidate, prepared accordingly. He became the first such debate contestant to practice with simulated TV conditions — lights, cameras, makeup and recordings of opponent’s speeches. Sessions were taped and played back. “I spent nine hours under the lights,’’ he’d recall.

Carter, conversely, pored over briefing books — even correcting typos and fixing grammar — but refused to participate in mock debates; they seemed contrived. Rafshoon recalls sitting with him at the hotel in Philadelphia, posing questions he might expect from the media panel. Instead of rehearsing his answers, Carter would just say, “I’ve got that.’’

When the debate began, Carter’s first question was a softball about the economy. He choked, giving a fact-laden answer with the spontaneity and enthusiasm of a robot. It was “as dreadful as one could possibly imagine,’’ in the subsequent opinion of his aide, Stuart Eizenstat.

But the debate would be remembered not for a human mistake, but a technical one. With more than half the nation's households watching, suddenly the sound went out. As technicians struggled to fix the problem, the candidates stood there for 27 minutes, not talking, not moving, not even glancing at each other. Now they both looked like robots.

Ford staffers rushed to the theater lobby, where press secretary Ron Nessen knew TV reporters would be congregating, hoping for something to air. Nessen happily complied, stressing how well Ford was doing. It was, he now says, “the first ad hoc spin room.’’

Ford, by most accounts, won the debate. Carter, expected to be the better TV performer, later said he felt overwhelmed; he’d never even met a president before.

The second debate would focus on foreign policy, Carter’s supposed weakness. “If one of us makes a mistake, that will be damaging,’’ he told reporters. Equally prescient was an earlier Carter campaign memo that cautioned against attacking the president: “Ford has to beat himself.’’

He did, about 20 minutes into the debate. Ford was asked about the 1975 Helsinki Accords, an attempt to improve relations between the Communist Eastern Bloc and the Western democracies that was unpopular with many Americans of Eastern European descent.

What Ford meant to say: We don’t officially accept or diplomatically recognize Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.

What Ford actually said: "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and there never will be under the Ford administration.’’

The questioner, Max Frankel of The New York Times, appeared unable to believe his ears. He gave Ford a chance to reverse himself: "Did I understand you to say, sir, that the Russians are not using Eastern Europe as their own sphere of influence?"

Ford dug in deeper. "I don't believe that the Romanians consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. I don't believe that the Poles consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union."

Ford’s national security advisor, Brent Scowcroft, was backstage. “We have a problem,” he said.

Carter pounced: “I’d like to see Mr. Ford convince Polish-Americans and Czech-Americans and Hungarian-Americans that those countries don’t live under the supervision and control of the Soviet Union behind the Iron Curtain.’’

Then the debate moved on. It seemed the moment might pass. TV anchors, including Walter Cronkite on CBS, did not feature the comment in their recaps. In Ford’s limousine afterward, Nessen says, no one mentioned the gaffe. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called to compliment Ford on his performance. He went to sleep thinking he’d done fine. “There was no red flag,’’ Nessen recalls.

Damage becomes clear

But the next morning the papers were full of stories about Ford’s gaffe. Carter was on the attack. Polish-Americans were in an uproar.

Nessen went to see Ford to urge him to “clarify” — admit his mistake. “I’ll never forget how he looked or sounded,’’ he recalls. “He said, ‘I’m not inclined to do that.’’’

Several days later, with the gaffe dominating campaign news coverage, Ford finally backed down — off camera — and admitted he’d misspoken.

The damage was done: Ford the debater was Ford the bumbler that Chevy Chase portrayed on Saturday Night Live.

Nessen says he’s never understood why Ford didn’t correct his error and cut his losses. Nor does Mondale: “He was a good friend. I never asked him.’’

In his memoirs, Ford wrote, “I can be very stubborn when I think I’m right, and I didn’t want to apologize for something that was a minor mistake.’’ The more aides asked him to, the angrier he got. “I don’t know why I was so stubborn,’’ he confessed.

Before the debate Ford was gaining fast on Carter. Afterward, recalled Ford pollster Bob Teeter, “We were stopped cold.’’

Still, it’s impossible to blame the gaffe for Ford’s defeat. At the end of October, polls showed the two candidates in a dead heat. And scholars agree that most presidential debates don’t have a major impact on general election outcomes.

But a debate performance can shape a reputation. On YouTube, George H.W. Bush (1992) will forever glance impatiently at his watch. Al Gore (2000) will always exude petulant sighs. Richard Nixon will always have a 5 o’clock shadow.

And Ford will always deny Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. But for a quarter century now, he’s been right.

More elections coverage from USA TODAY

• Quiz: How much do you remember about the 1976 election?

• Quiz: Test your memory of general election debates