3.7-billion-year-old fossil makes life on Mars less of a long shot

And you thought that slime in the bottom of your fridge was ancient.

Scientists have found the oldest known remnant of life, a fossil dating back a staggering 3.7 billion years. If confirmed, the date would support the theory that life took root in just a blink of an eye after the planet’s birth. Such early life would also make life on Mars seem less of a long shot.

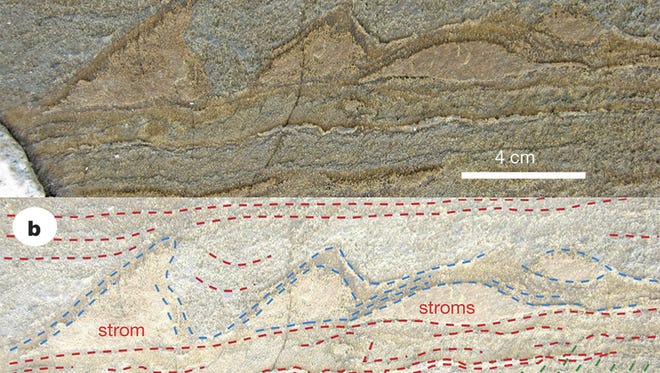

The newfound remains consist of a layer of rock that, to the untutored eye, looks, well ... like a layer of rock. Scientists say it’s actually a stromatolite, a mineral structure created by the busywork of countless microorganisms. These microbes thrived in a shallow sea bathing a still young and fresh Earth, according to a study in this week’s Nature.

Previous chemical analysis of old rocks hinted life arose by 3.7 billion years ago, but that evidence was open to question, says study co-author Allen Nutman of Australia’s University of Wollongong.

“What we’ve done is produce something tangible,” Nutman says, “an actual fossil record (that is) evidence for life at those times.”

The researchers “were able to see evidence for life in a way that I had never expected,” says Texas A&M University’s Michael Tice, who was not associated with the study. “We have a much better window back in time, thanks to what these folks did.”

The fossil was discovered in a barren stretch of Greenland that researchers have patiently explored for some three decades. Unusually heavy spring rains recently melted a longstanding snow patch, exposing a distinct layer of rock.

The rock layer contained a level bottom, but the top was jagged. Standing less than two inches high, the layer resembled a miniature mountain range in profile.

After having read extensively about such objects, “we immediately knew what we were looking at,” Nutman says. That jagged top suggested not just a rock but a rock born of biology.

The rock’s structure mimics that of a 2-billion-year-old object widely accepted as a stromatolite, says study co-author Martin Van Kranendonk of Australia’s University of New South Wales. Chemical clues also hint that microbes played a role in the object’s formation.

The structure of the rocks around the fossil suggests it was bathed in seawater. Beyond that, the team knows nothing of the stromatolite’s origins. Modern stromatolites — such as the famous mushroom-shaped examples at Australia’s Shark Bay — are built by crowds of bacteria and other single-celled microbes. But the identity of whatever was living 3.7 billion years ago is obscured by the altered state of rock from that era, which over the eons has been cooked and twisted beyond recognition.

More study of the stromatolite is needed to confirm the fossil’s identity, says Abigail Allwood of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, author of an accompanying analysis for Nature.

But if it is confirmed, “that says to me that life is not a fussy, reluctant, unlikely kind of thing,” she says. “Give it half a chance, and it’ll run with it.” After all, asteroids had bombarded the Earth only 100 million years earlier, but life still blossomed, spread and grew sophisticated by the time the fossil formed.

Parts of Mars looked much like the area where the stromatolite took shape at roughly the same time, Allwood says. Until now, scientists wondered whether the lakes on Mars persisted long enough for life to spring up, but now, she says, “what we’re potentially seeing is evidence that life can get a foothold in such a short time frame.”